Password crackers don't guess, they just try

Crafting good passwords without knowing how they’re cracked is like crafting good locks without knowing how they may be picked.

I propose here a quick introduction on what password crackers are, and how they work, so that you’ll know a little better what you’re fighting against.

Password cracker mechanism

A password cracker can’t actually guess your password out of thin air, it needs a clue to work on. And if you remember, the only lead to your password that remains on the computer is… its hash. So to crack a password, we need to get its hash first, wherever it is stored.

This is not a problem if you have a physical access to the computer, but it’s far more challenging to perform from a remote access. It is however very possible, and it happens regularly, even to safety guards like the password manager LastPass, which was hacked in 2015. Hackers were very likely aiming user hashes.

More specifically, the location of password hashes depends on the operating system you’re running on:

- Windows:

"C:\Windows\system32\config\SAM" - Linux:

/etc/passwdand/etc/shadow - Mac:

/var/db/dslocal/nodes/Default/users/username.plist

In any case, they’re just text files: they can be read directly, if you have access to them. Once again, it’s very tricky to remotely do so, but feasable, and anyway quite trivial from a physical access, providing the hard disk isn’t encrypted, which is not the case most of the time.

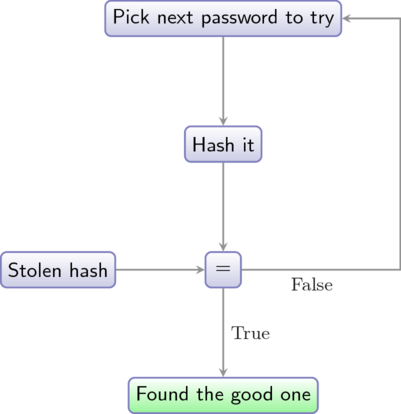

However, once we get a password hash - we’ll creatively call it the stolen hash - there’s still a major issue: hashing is a one-way function, which means there is no calculation enable to turn this hash back to its matching password.

The only thing that can be done is what you computer does during password certification: pick a password, compute its hash, and check it against the stolen hash. If the hashes are equals, it means the checked password was the good one.

Well, that’s all. A password cracker is merely a piece of software that generate a whole bunch of passwords, compute their hashes, and check each and everyone of them against the stolen hash. If one of these passwords matches, it means it is the password we were looking for.

A password cracker is hardly a hacking tool, more a mere hash calculator and comparator.

Pick the lock or find the key

A common misconception is to think that password crackers directly crack Windows sessions, or website accounts, as if we were tricking them into dropping the password, or by entering passwords until the session opens.

This is actually not possible, because systems have safeguards to prevent such attempts.

A basic protection, which can be found for instance on SIM cards or Windows Enterprise, is to lock the account should too many failed attempts happen, generally three. As a password cracker might need to try millions of passwords, it would lock the session far before finding the good one.

I’m not a big fan of this protection, because we all end up locking our own session, not having spotted our Caps Lock was on…

A better solution - now enforced in any decent system - is to enforce a temporization. Each time we enter a wrong password into our system, it will wait a little before enabling us to try again. It can be a short wait, like one second, which is not very disturbing for us, but dreadful for a password cracker, as in the period it has to wait, it would have been able to try a million password. Thus it’s slowed down in its guessing process by a factor of one million.

By the way, temporization is enforced per se for website accounts, because of the network latency, which prevents brute-force attack on servers. Well… actually it’s done, but it’s called a Deny of Service Attack which aims at crashing servers rather than getting information. No use for our password cracking situation.

Password crackers don’t pick the lock, they can’t. They just try to find the key, and then open the lock with it.

Hacking strategy: choosing passwords to try

We’ve seen that password crackers just try passwords, and check their hashes against the stolen hash.

That’s not so easy though, because testing every single password is impossible. There are too many of them, an infinity actually.

As a result, the hacker needs to think ahead and define a hacking strategy, which consists in figuring out what passwords should his password cracker try.

Here’s the three most commonly used techniques.

Brute-force

A brute-force attack basically consists in testing every single combination.

If we were cracking a 4-digits combination-lock padlock, we would brute-force it by trying 0000, 0001, 0002… up until 9999. We could do it manually with some patience, let’s say one try per second, so almost 3 hours. A computer does it almost instantly.

If we were cracking a 8-long password composed only with lowercase characters, we would try a, b… z, aa, ab, ac… zz, aaa, aab… zzz, aaaa… aaaaaaaa… zzzzzzzz. Obviously we couldn’t do it manually anymore, as they are 208.827.064.576 different combinations. An average computer however could try them in a couple of day, assuming it can perform 10,000,000 guesses per second. A good computer, or a cluster of computers working together, can perform 100,000,000 guesses per second, so only half an hour would be necessary.

But passwords are not limited in length, and can contain lowercase and uppercase characters, digits and symbols, for a total of 96 typographic signs. As a result, the number of combinations for a password of length N is 96^N.

A 8-long password has now 7.2 quadrillion combinations, and trying each one of them would take more than 2 centuries on an average computer, 23 years on a really good one, which is… quite deterring.

As a result, brute-force attack is only suitable for cracking very short passwords, namely inferior than 8 characters. Though, a lot of commonly used password are below that length, exposing the accounts they protect.

Hackers with little computing resources might not be able to crack complex 8-long passwords - although they might with some patience. But those passwords are absolutely not secure against wealthy groups with a lot of computing power.

Three years ago, a SLI cluster - several graphic cards working together - proved to be able to brute-force any 8-characters password in less than 6 hours!

Don’t use passwords shorter than 8 characters… never.

Dictionary

A dictionary attack is a smarter approach. It relies on the simple assessment that a lot of people use the same passwords.

Sadly, passwords like 123456, football, qwertyuiop or starwars are still on the top list of most commonly used passwords.

As a result, we can get a list of the most commonly used passwords, and just check them against our stolen hash. There are a lot of these password lists around the net. A lot of them are free of charge, although they may be less comprehensive, and already encompasses millions of most commonly used passwords.

This method is more statistically efficient than brute-force attack, because it takes into account user habits, and does not limit itself to 8 characters passwords.

Be sure not to use a password that is likely to have been thought of by others.

Rainbow table

Rainbow table attack is a slight improvement on dictionary attack. When performing a dictionary attack, we still need to compute a hash for every single password contained in the dictionary, which is very time-consuming. In contrast, comparing two hashes is a very quick task.

As a result, we would prefer to have a pre-computed hash along with the password in a lookup table. That’s basically what a rainbow table offers: it directly provides the hash corresponding to a password, or rather a password corresponding to a hash.

That way, for a stolen hash, we only have to look in our rainbow table if this hash exists. If it does, the rainbow table immediately provides the corresponding password, which is the one we were looking for.

If your password is one of those available in rainbow tables, be sure it won’t take a lot of time to crack it.

Combine this approaches with social engineering

Previously mentioned tactics do not rely on any personal information: they do not need to know who you are to try to hack you. Paradoxically, it is a weakness, because the more you know about someone, the more you can use against him.

That’s why it’s said friendship is to be granted with great care: you give them weapons assuming they’ll not use them to hurt you. That’s also why Facebook’s use of the word “friend” is highly dangerous and prone to misguided behaviours. But saying “I have 297 acquaintances!” is surely less sexy.

In a hacker perspective, intelligence about your target can be used to crack his password. The assumption here is that people use personal data to create their passwords.

Personal data does not necessarily mean private data, but rather encompasses both public and private data, as long as it’s something that identifies you.

Such intelligence can be: first name, last name, pseudonym, birth date, birth name, pet name, city of birth, current city, favorite everything (animal, actor, character, music band, song, movie, place, color, …), job title, brother name, … and so on.

For instance, if we were to specifically hack someone called Sophie, we could use either a brute-force or dictionary attack, but adding to it the specificity about Sophie. We could try any kind of combination containing Sophie, Soph, Sof, Soph1e, … and compute various combinations, adding letters, digits or symbols: Sohie0145, !SofPwd7894, S0ph1E38004, …

Computers are very good at creating millions of these variations, so they might be able to find a match, especially if they do not use only the name but all we could find on our target.

Furthermore, as a lot of these data can be found on the internet, it has become easier than ever to do so…

Watch out what you publish on the internet. Consider any information you released is no longer suitable as password material.

For the sake of clarity, I’ve made some small approximations. For instance, a same password can have two different hashes, thanks to a process called salting. So in order to use a password cracker, you’ll need to retrieve both the password and the salt. Read wikipedia for more info.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.